PUBLISHED JULY 21, 2022

Stephanie Vargas Maldonado

Stephanie Vargas Maldonado is a graduate student in the American Indian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is a first generation college student who grew up in Boyle Heights, East Los Angeles. Her research interests include Mesoamerican ethnobotany, language revitalization, ancestral medicine, and plant knowledge. She centers her work on Zapotec healing and the experiences of the Zapotec diaspora in Los Angeles.

My maternal family is Zapotec from El Nigromante, Veracruz. My great grandfather, Toribio, was a yerbero (herbalist).

As a first generation college student living in East Los Angeles, I found myself disconnected from my identity, my ancestors, and the natural world. I yearned to reconnect with Zapotec cultural practices, seeking a better understanding of ancestral medicine.

As children, my sister Karina and I climbed the níspero tree outside our home in Chiapas, Mexico, to collect its fruit at the very top. The níspero tree was our playground and snack bar. Karina, being older, usually climbed a few branches above me for “safety.” Once, while climbing, my sister’s foot slipped from a branch and her body onto mine. We landed on the ground, feeling dizzy and our backs aching from the fall. Since then, we have been satisfied with the níspero we could reach from the ground. The níspero tree that brought me joy is a part of Zapotec plant medicine. Although I did not grow up knowing the significance of níspero, I have reconnected with Zapotec culture through plant knowledge, allowing me to appreciate plants for more than their visual appearances and wonder about their healing qualities. Doña Enriqueta Contreras, known as Doña Queta, a Zapotec curandera (healer) and partera (midwife) explains that níspero leaves and flowers can treat diabetes, circulatory problems, lower arterial tension, and cure liver illness.

Zapotec plant medicine emphasizes la madre naturaleza (mother earth) as the source of health and wellness. Zapotec people of Sierra Norte, Oaxaca, known as the “People of the Clouds,” recognize that the Earth provides medicinal plants, confirming the importance of traditional medicine. Curanderos remain highly valued in Zapotec culture for their ability to treat people medicinally with plants.

Figure 1: Nispero tree leaves (eribotrya japonica)

So how do we approach valuing ourselves and the natural world? How can we be respectful in interactions with plants when using them for medicine? How can we acknowledge the sacrifice and effort of Mother Earth to make life possible? Zapotec knowledge and Doña Queta suggest that listening to Mother Earth is the foundation:

“La madre naturaleza…Aprendí que si la escuchas, te enseña a valorarte como ser humano y a tomar conciencia de que cada ser humano tiene su valor, porque todos somos uno y porque también somos uno con la naturaleza, somos un solo cuerpo.” (Falcón, 2009, p.13)

“Mother earth…I learned that if you listen to her, she will teach you to self-worth as a human being and take consciousness that each human being has their worth, because everyone is one and because everyone is also one with nature, we are one body.”

Doña Queta emphasizes self-respect, reflection, and connection to the Earth as essential to our consciousness. She advises people — especially young people — to contemplate: “Who am I? What is my worth? What do I want for myself?” She affirms that change must begin within ourselves, that inner peace enables outer peace and vice versa.

Like the níspero that grew in my backyard, the maguey, a type of agave, is commonly found in the Oaxaca Valley. The heart of the maguey, sometimes known as dohb or dob, is an ingredient used for cooking and making mezcal. After Spanish arrival, pulque maguey, an alcoholic drink made from the sap of the maguey, was exploited as a commercial crop. Growing agave, especially maguey variety, is a long term investment that matures over twelve years. From El Silencio to Casamigos, mezcal is an in-demand liquor in Mexico and the United States. Aside from its economic features, mezcal has influenced popular culture through songs like La Ley del Monte by Vicente Fernadez and novelas like Destilando Amor that romanticize maguey. But, maguey is more than its economic performance and Mexican iconography. Maguey has medicinal properties that Doña Queta explains to be found in la penca (leaf), espinas (thorn), flor (flower), and tayo (stem).

There is more to the maguey than a fun night out. Doña Queta shared that maguey is a medicinal plant. The thorns of the maguey can be used to open infections and as needles in acupuncture-like applications to relieve back pain and low energy. Placing four espinas around the belly button in the four cardinal directions can help an individual after throwing up by releasing excess gas. To this day, some Zapotec people consider mezcal a sacred drink used as an offering to la madre tierra when constructing a house, planing maize, and for an abundant harvest. Doña Queta explains that all types of maguey can be used for healing. For example, mezcal can help healers extract bad energy, cure el chanque, a spirit that captures a person's soul from fright or sadness, and relieve susto, a condition that occurs from a sudden shock, fright, or accident. Using mezcal, chupador healers suck the skin in which the first inhale can take out blood and the second inhale can take out something strange, like an object.

Zapotec plant knowledge classifies herbs and illnesses as having “hot” or “cold” qualities: illnesses classified as “hot” are treated with remedies classified as “cold,” and illnesses classified as “cold” are treated with remedies classified as “hot.” Though some scholars think this “hot” and “cold” system may have originated from India, some 3,000 years ago, many scholars agree that the system was introduced by Spanish priests and is continued to be practiced throughout Mexico. Importantly, the Mesoamerican hot and cold system does not necessarily refer to temperature, but rather hot and cold are energetic characteristics. For example, empacho, indigestion and stomach ache, are considered “cold” conditions that should be treated with “hot” remedies. Understanding a plant's hot or cold characteristics helps determine the proper remedy. For cures with multiple herbs, it is advised to know how a cold and hot plant affect the remedy to be multiplicative, meaning ingredients in one plant element may enhance the other plant’s properties. San Juan Gbëë, a Zapotec community in Oaxaca, Mexico consider certain plants to be characterized as “cold” or “hot,” and Mixtec communities tend to classify illnesses as “hot” or “cold.” While the “hot” or “cold” rule is not strictly enforced, it is often used as a treatment guide.

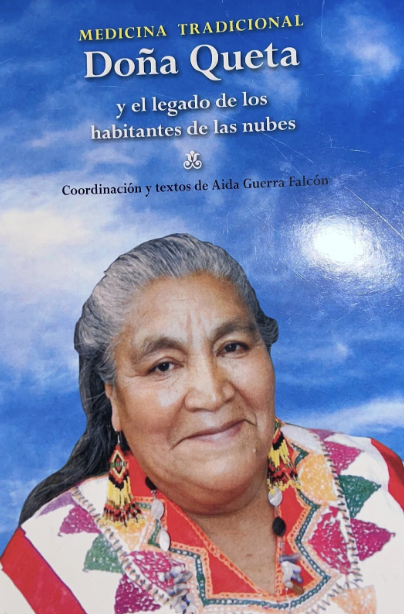

Figure 2: Medicina Tradicional: Doña Queta y el legado de los habitantes de las nubes by Aida Guerra Falcón.

Zapotec plant medicine relies on connections between people and the land. The “hot” and “cold” systems, and uses of maguey, are examples of how Zapotec plant knowledge lives on through generations; knowledge that is preserved through people like Doña Queta. My own process of learning about Zapotec plant medicine has encouraged me to think about what knowledge my ancestors, like my great grandfather Toribio, would share with me. Though I never got to meet Toribio, I gained some of his wisdom through the collective knowledge sharing of Zapotec healers.

Bibliography

Contreras, E (2016, Apr 16) Interview. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kpfl9xFsDhg

Contreras, E (2016, Oct 26) Interview. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAYQS7Vob9o

Contreras, E (2019, Sep 23). Interview. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lqypv-TaxfM

Contreras, E (2020, May 3). Interview. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e4441uJQ6bM

Falcon, Aida Guerra. (2009) Medicina Tradicional: Doña Queta y el Legado de los Habitantes de la Nubes. Oaxaca, México.

Hunn, Eugene. (2008). A Zapotec Natural History: Trees, Herbs, and Flowers, Birds, Beast, and Bugs in the Life of San Juan Gbëë. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Smith, C. E., & Messer, E. (1978). The Vegetational History of the Oaxaca Valley and Zapotec Plant Knowledge (K. V. Flannery & R. E. Blanton, Eds.). University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11396149.

Martinez, Candy (n.d.). Latin American And Zapotec Views On Susto. The Archive of Healing. https://archiveofhealing.com/Susto.